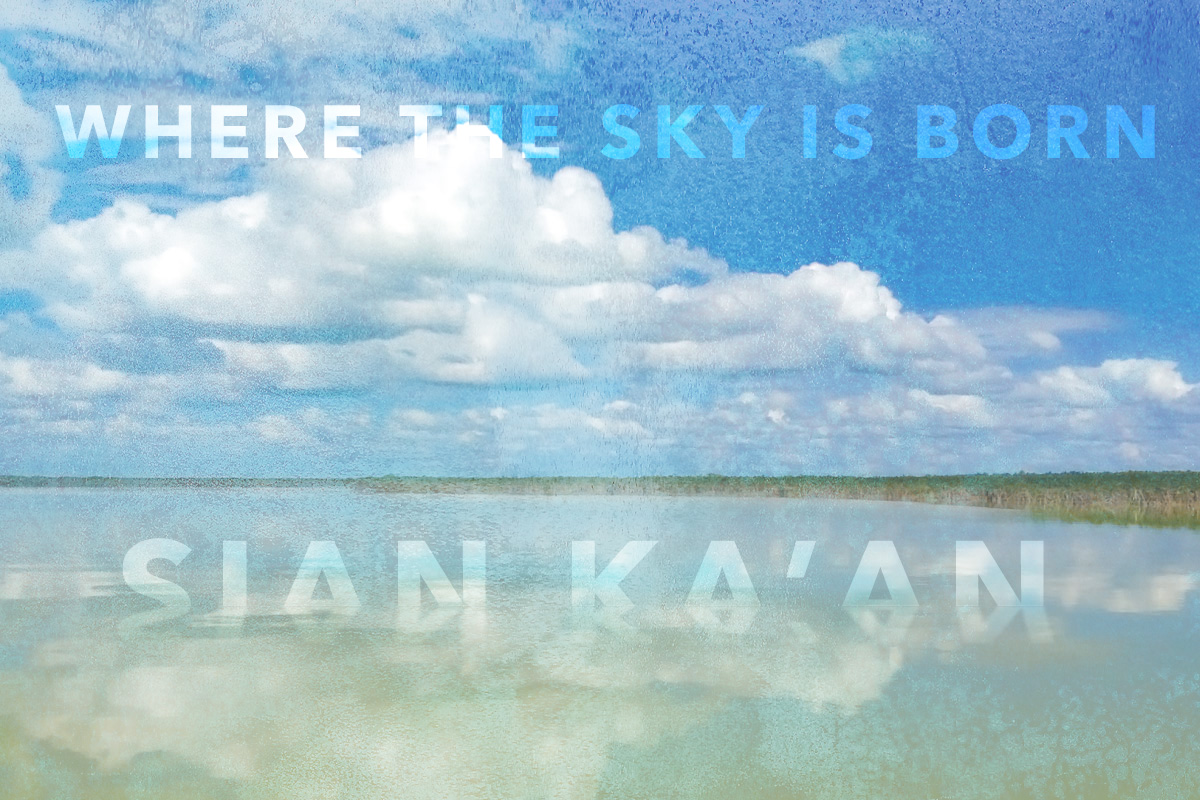

Where the Sky is Born

Getting Lost in the Mangroves: A Sian Kaan Biosphere Reserve Mexico Bonefish Kayak Fly Fishing Expedition

Thoughts of my final days in Tulum ebb and flood in my brain as I navigate my way over hidden topes (speed tables) and around wandering dogs. I knew this last day in the mangroves fly fishing the Sian Ka’an would come. This biosphere reserve is a unique treasure and its massive lagoons and limitless mangrove waterways sit less than an hour to the south down a long, bumpy road on a lengthy sliver of land called the Boca Paila Peninsula. During my winter stay here in the Yucatán this place and its mystique has intertwined itself into the fibers of my soul. A Sian Kaan Biosphere Reserve Mexico bonefish kayak fly fishing expedition will be one to remember.

“He could not live without adversaries, no more than a tree can live without soil; like mangrove trees, which make their own soil, he could create enemies from within himself.” – Peter Evans.

Daylight only hinted at its eminent arrival as I cranked the Toyota’s engine. It was 5:45am. After undoubtedly waking my humble little apartment complex I worked my way through town. I was ready. The truck was packed with the necessary gear: 8wt fly rod and reel, extra 8-20lb leader material, bonefish flies, snips and forceps. As always, my Advanced Elements inflatable kayak was neatly folded and stored behind the bench seatback along with the pump and paddle. So far, the little boat has done me well here in Mexico.

“If there is magic on this planet, it is contained in water.” – Loren Eisley

Taxi cabs race the streets and highways day and night in Tulum. On this morning, as I approached the coast and Tulum’s hotel district, the fortuitous fleet jockeyed for position as they would any other time of day. Each one hoped to get the first crack at the early birds. Lately, I’ve been able to keep pace with these speed demons. I think my time in Mexico has toughened me having grown accustomed to dodging 5-passenger scooters, stray dogs, invisible speed bumps and the vast mine field of potholes. Funny… there’s a comfort in the chaos down here.

The hotels were quiet at this early hour. The pavement turned to dirt as I left the comforts of hotel row and entered the Reserve. As I negotiated holes in the road I pondered what would, surely, be a quiet day on the water. Peace and creativity are integral parts of my life… the doc told me so. I went to a doctor in Tulum. First thing he did: he looked at my palms. He told me that I NEED to be creative… that I NEED to be at peace. Amen to that! I knew where I needed to find solace. I think I’ve always known. Peace, for me, often comes in the form of water—a river, a lake, an ocean, an estuary. Maybe water is my medication. Relief lay just ahead.

Great plumes of dust billowed from behind the truck. My destination was near as the sun rose brilliantly from the Caribbean. I parked the truck just beyond the Boca Paila bridge as I had done several times before. I inflated the boat, rigged the rod and slipped into the lagoon. The ebbing current was strong. It was like clawing your way up a sand dune. Massive amounts of water drained from the lagoon back into the ocean. Below the kayak schools of juvenile fish raced by. They moved down-current toward the narrow corridor in hopes of safely returning to the ocean after a night in the sanctuary of the lagoons. In the shallows I noticed a few stingrays effortlessly cruising the sandy substrate. They appeared to have no particular destination. I didn’t miss the car horns in Tulum nor the omnipresent music from the strip club next door to my apartment. Still, this moment on the water was unnervingly quiet except for the few birds within the twisted mangroves. A heron’s head peaked out from the canopy and peered in my direction. Apparently he saw this wayward stranger as a threat and launched into flight squawking its disapproval. Only having seen one in all my visits here, I sensed the presence of the resident (and luckily, nocturnal) crocodiles lurking just beyond view. As always, they are kings of the mangroves.

The lagoon opened into wide, shallow flats with various shades of blues and greens on display, not yet showing its full, vibrant grandeur in the soft, morning light. I quartered the light wind and made for the distant mangroves across the lagoon more than a kilometer away. I’ve trolled this section in recent expeditions and caught jacks, bonefish and barracuda. It’s the latter I fear. In reality it’s my flies and leaders that fear the barracudas and their razor teeth. I refrained from trolling, hoping to save my rig for the “bones”. These lagoons of Sian Ka’an sustain a vast and diverse ecosystem vital to all life here in the Riviera Maya. I am truly blessed to experience it.

Established as a reserve in 1986, Sian Ka’an Biosphere Reserve is also a UNESCO World Heritage site. At 1.3 million acres, it’s the largest protected area on the Mexican Caribbean. There are even Mayan ruins hidden within its dense forests, 23 of them known. It is aptly named—“Sian Ka’an” translates to “where the sky is born.”

“Come forth into the light of things. Let nature be your teacher.” – William Wordsworth

The cool breeze subsided and the sun’s heat intensified as I finally entered the solitude of the mangrove forest. Its low-lying vegetation hid my profile. I had previously witnessed flats boats motoring swiftly through these same mangroves with only the captain, positioned high on his perch, visible above the canopy as he scanned the water. As far as I knew, I was the only human for miles on this day. I meandered the maze northward hoping to find secluded flats. Have you ever driven in an unknown place and gotten lost? Have you then continued to make wrong turn after wrong hoping to find your way while getting even more lost? This mangrove ecosystem is an unknown place. I got lost. What appears to be a “through” water course would often result in a dead end. After a few dead ends, I decided to follow the path of those who know the area best. With a smatter of reluctance, I followed the serpentine imprint from a crocodile’s tail. The imprint led me into ankle-deep water. It was there that I noticed large, reptilian claw prints next to the tail markings. The croc must have clawed and pushed its way through to deeper water. Sure enough, the crocodile knew the path of least resistance and, sure enough, I found myself in the northern reaches of the lagoon. Score.

The constricted course opened to an expansive, circular flats section the size of a couple futbol fields. There was a dense, well-established mangrove island smack-dab in the middle. I moved with the stealth of a ninja. At least I did in my mind. In reality I was more like a bull in china shop. Very aware of my presence, a pair of large wetland birds called American white ibis’s quietly observed my antics while keeping an eye on the water for their next meal. They had nothing to say. Moments later, like a torpedo-shaped, silvery blur swam straight at my bow. It was a barracuda. At the last moment the fish darted at a 90 degree angle away from me, stopped abruptly and positioned its body as if to size me up like a cat ready to pounce. It remained in that strike position until I passed. They are feisty fish with big, toothy grins. I continued on in search for the elusive bonefish. Either my eye wasn’t trained well enough or there really weren’t any in the fringes of the lagoon.

Eventually I found a patchwork of small coves with ideal bonefish habitat and perfect, wadeable flats. There was only the slightest of breezes. The water was glass. The midday sun was high above. Visibility was remarkable. And, there they were: multiple schools of 12-16 inch bonefish actively hunting the open flats occasionally venturing into the more sparse mangrove borders. On the flats, they made their rounds in groups of five or more, stopping once in a while to collectively and aggressively dip their noses into the sand, the tips of their tails exposed just above water’s edge. They were on the search for food. Being opportunistic feeders, they’ll eat just about anything they find under the sandy substrate: crabs, shrimp, clams, snails, worms, etc. When they find less willing prey, their activity usually increases with lots of splashing at the surface. It had the appearance of a buffet for a fly angler.

“The fishing was good. It was the catching that was bad.” – A.K. Best

In the past few weeks I’d had better success targeting single bonefish, or even pairs. These active groups intrigued me. They beckoned. I chomped at the bit to send a fly their way. In hopes of matching the substrate, I decided to use a yellow shrimp pattern with black stripes called a “Gotcha”. After securing the kayak to the mangroves, I stealthily inched within about 60 feet of the most active area on the flats. I felt invisible. They knew I was there but continued as if I wasn’t. Maybe they were just being nice. Determined, I cast the fly into one school’s path of travel, letting the fly sink to the bottom. I watched, waited and felt. The clever school veered away from the fly at the last moment, even after I gave it a subtle twitch. A minute later they started tailing and nose wedging into the sand about 50 feet from me. I cast right next to the activity and gently stripped in some line. Nothing. Next I cast right in the middle of the tailing fish. Nothing. I tried a different fly… this time a white “deceiver” with some flash. Nothing. I tried multiple fly patterns, multiple approaches and multiple techniques with the same result. The winds eventually picked up and the water whispered, “not today.” It was time to make way and head back to the trusty old pickup waiting for me at the put-in.

What seemed like minutes on the flats was hours—nearly seven hours. For the first time since I arrived at my temporary home on the Riviera Maya I got skunked. My parting gift: memories of pure, aquamarine bliss. These will do.

Story and Photo by Brock Munson

cofounder • Chasing Scale

Brock is the lead writer at Chasing Scale • brockmunson.com